The Story of Edwin Murphy Hill

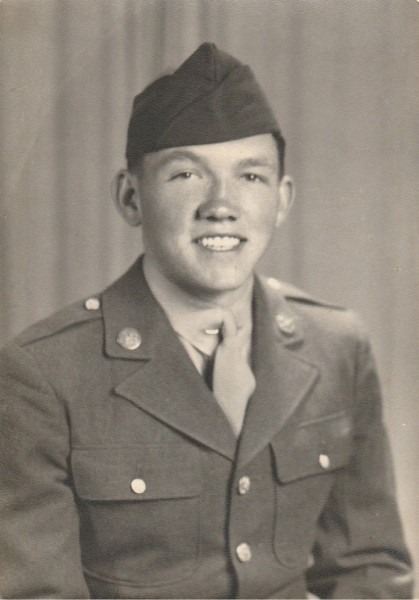

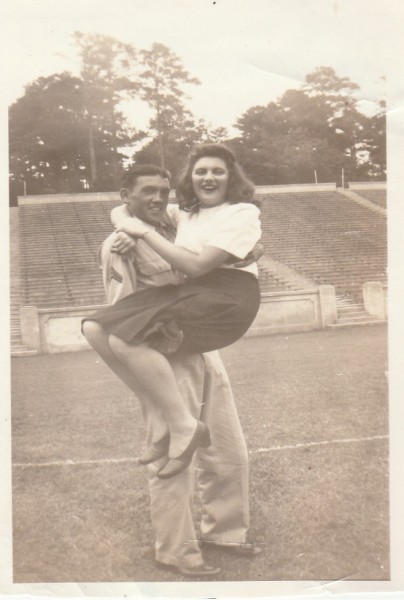

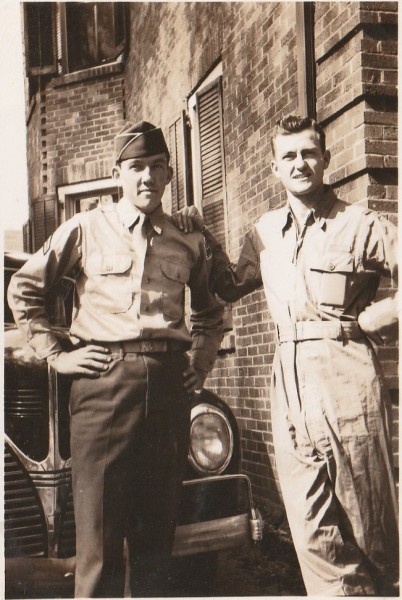

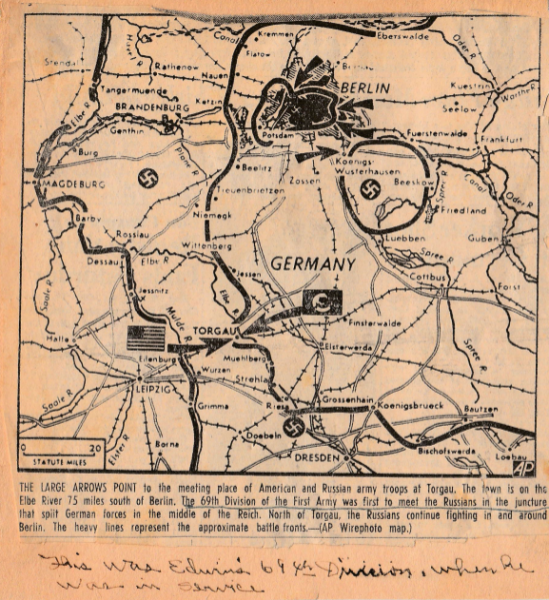

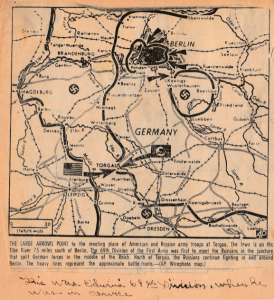

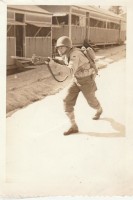

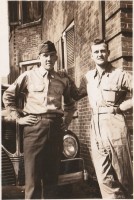

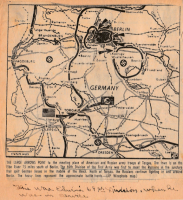

On 25 April and 8 May 2020, we will celebrate the 75th anniversary of two historic events from WWII: the famous American-Soviet linkup between elements of the 69th Infantry Division and Soviet troops at the Elbe River in Germany and VE Day. Below is a story about one such soldier who contributed to the lead up to both historical events.During World War II, 361,000 North Carolinians served in the armed forces that included 258,000 in the army. One such Tarheel was my maternal grandfather Edwin Murphy Hill from Walnut Cove NC. He served in the 271st Infantry Regiment, Company G, of the Fighting 69th Infantry Division earning a Combat Infantry Badge, European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (with two bronze service stars), the World War II Victory Medal, Army Good Conduct Medal, and a Purple Heart.

I recently completed the yearlong project to transcribe nearly 300 letters my grandfather wrote between 19 April 1944 and 12 November 1945 to his girlfriend and eventual wife (my grandmother), Ms. Joy Jean Flynn of Walkertown NC. Through this intimate process, I learned how much the letters from home were an essential part of my grandfather’s existence and how the daily mail call routine would impact his psyche while marching his way through Camp Shelby for infantry training, Camp Kilmer where the 69th prepped for deployment overseas, through the hellish days fighting in the European Theater of Operations (ETO), recovery from hepatitis sickness in a British hospital, and his final convalescence period at the US Army’s Battey General Hospital located in Rome Georgia prior to his formal discharge on 17 November 1945 at Ft. Bragg NC.

Mail call at Camp Shelby was described as the following:

“But the best was mail call. Somebody would yell, “Mail” and at once be surrounded by a widening circle of expectant faces. Maybe you got a letter and maybe not. If you didn’t get one you would wait until the last letter was called and then look on the ground to see if possibly one had been dropped. You wanted mail—any kind of mail, anything from home. It could be a letter from the girl or your mother or the kid sister, or even a bill from some hometown store. Anything from home! And when you got it you went off into a little world of your own while you read it—a world far removed from this new harsh army world. Maybe you sat on your bunk to read it or you went off to an empty drill field and sat under a tree. First you opened it, and if you were like most soldiers, you had a special way of opening a letter. You didn’t rip it open; you went about it slowly, savoring every happy moment of it. You looked the outside over, slowly reading the postmark, the return address, noticing the color of the ink and the exact style of handwriting, and wondering just what was inside. And then, when you could wait no longer, you tore open the envelope and plunged into the words from home.”

When referring to the importance of mail delivery during WWII, Frank C. Walker, the then Postmaster General of the United States remarked “It is almost impossible to over-stress the importance of this mail. It is so essential to morale that army and navy officers of the highest rank list mail almost on a level with munitions and food.” Letters from home provided my grandfather a mental sustenance to cope with his wartime experience. He himself cited “morale” 54 times in his letters as either high or low depending on the results of the mail call—reinforcing the prescient statement of the Postmaster General. His need for mail from his “angel”, “sweetheart”, “honey”, “darling”, “Coves girl” and “pin up girl” along with the “home folks” in “dear old Carolina” was a central discussion of every letter he wrote and when he did not receive mail it was devastating. He used the term “blue” over 60 times when describing his emotional state when no letters arrived during mail call. Below are two excerpts from letters written in December 1944:

“Somewhere in England Sunday Nite Dec 3”

“Was a very blue day today cause we had a mail call and I didn’t get a line from a soul. Gosh it almost makes me sick cause when we heard that we would have a mail call my poor heart was really happy for I figured at least I’d hear one letter from you but when I didn’t hear my feelings were certainly blue. Honey I know you are writing but see our mail has to be handled and censored so much till it takes a long time for our letters to reach each other. Jean honey I’ve written you every day since I’ve been in England and just long as we aren’t in combat I’ll write every day unless something else comes in the way. There is nothing I’d rather do than sit down and talk to you by means of these letters and I feel so close to you while writing, it makes me feel good. That’s all right darling I’ll be looking forward to our next mail call with even more hopes. As long as you and I write every time we possibly can, everything will be all right with the mail.”

“England Dec 6th Wednesday Nite”

“Darling I only wrote two or three times on the boat coming over cause I was pretty sick, but I have written every day since I’ve been in England. Will do my very best to write everyday while I am away from you. Ok? If you love getting my mail as I do your precious letters, well I know how much they really mean to you. With my honey, when I get your letters, I am just thrilled to death. And then when we have mail calls and I don’t get one as the case was today, I am so darn blue, I could just cry if that would help me feel better. Am always looking forward to just get your mail for there is 99 9/10 of all my morale.”

When assessing the entire correspondence collection, I realized what made these letters so special was not gory details of battle or combat atmospherics but instead a remarkable narrative of a young man in love and who loved his family and friends dearly. His letters are a window into the soul of a youthful American boy who was certainly scared about his future but never admitted it. He was truly fixated on orchestrating his relationships with Jean, his parents, his siblings, and friends through each letter with a surprisingly upbeat, positive disposition. One way I could gauge his contentment was when he cited the word “jake” (used 2o times in his correspondence). This was a popular slang term that meant fine, good, well, or satisfactory. Typically, he would state “everything is jake” or “everything seems to be jake”. This optimism is what made my grandfather—like so many of his 69th brethren—part of the greatest generation who did much to faithfully fulfill his duty to country. He certainly endured hardship, saw dead and maimed bodies, and walked through scenes of horrific destruction but somehow his letters remained constant in expressing his love for Jean and “dreaming” of a future with her.

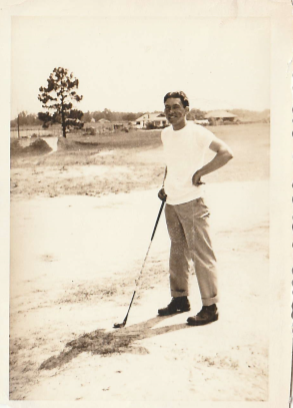

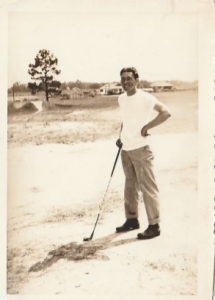

Many letters he wrote while he completed infantry training at Camp Shelby referred to the pressing military training as “problems” or “maneuvers” that were made more difficult by the “chiggers”, “mosquitos”, and the “terrific heat”. Despite the challenges, he still found time to play golf in Columbia or Hattiesburg and would also attend a dance or go to the movie theater for some well needed leisure time. He arrived at Camp Shelby in September 1943 with the rank of Corporal and by late August 1944 he was elevated from Assistant Squad Leader to Squad Leader. In late October 1944 Ed became a Sergeant just prior to his departure on the train ride to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey.

While he was courting my grandmother through these letters he also tried to keep up with his oldest brother, Byron, who served in the China Burma India Theater as a B-25 pilot eventually completing 59 missions and earning an Air Medal with one oak leaf cluster before returning to the U.S. in March 1945. While my grandfather wrote to Byron directly, he cited Byron 125 times in his letters often exchanging questions with my grandmother about his status. He also tried to keep up with his two younger brothers, Robert “Bobby”, who was stateside completing training to be a Navy pilot, and Charles “Chig” who was too young to enlist and remained home. His youngest sibling was his sister Sara Lou who he adored. While he certainly loved each of them Byron was always on his mind and since they were both serving overseas in different theaters and facing combat the concern of losing his older brother certainly weighed on his mind. My grandfather provided a unique and loving expression of his brother in a letter he wrote to Jean on October 2, 1944:

“Guess you always knew that he was the nearest brother to me by some humane blood or instinct. He just seems so close to me. Yes I love all the others just as much but its he (Byron) that I am always thinking? “Sure hope he is ok? And I can definitely say he has been wonderful to me since we grew up. I try to write him at least once a week!”

Obviously, soldiers are trained to kill but they often avoid talking or writing about wanting to kill another man and my grandfather was no different. He only used the word “kill” in a few letters. My grandfather like almost all the soldiers of the day were more fixated on the opposite sex even when trying to survive in combat conditions. In a March 12, 1945 letter, he provided an entertaining description of the local girl situation and the threat of U.S. soldiers being killed.

“Since have been in Germany have been in and near the combat action all the time, so you know we haven’t had a chance to look around. Have seen lots of very pretty German girls but it’s a “very strict” violation of the articles of war to even speak to a German girl much less to try and date one of them. Oh yes I did learn to speak a little French language and have picked up some of this German talk. As for the Belgians, they either speak French or German, they don’t have a native language. Lots of the boys are “souvenir” hunters but I don’t care to fool around with the captured eqpt. Because the Jerries love to “booby trap” the stuff they leave behind, and old Edd knows to keep hands off. Lots of the boys have been killed by fooling with their souvenirs.”

The only other mention of killing was where he discussed it as a reluctant action that he had to undertake to get back home. In a letter sent to Jean on January 15, 1945 from England—likely knowing he was a few days from entering France and one step closer to combat—he stated the following:

“Sure am hoping that old Byron gets home real soon cause I always worry about him and it would certainly be some good relief to learn he had been sent home and then should I go into combat I’d have a clear field to do nothing but think of my darling Jean (no. 1) and kill Germans, have always hated to think I would have to kill a man but once I am in the big show, its then “kill or be killed”. And sweetheart this old boy is going to do the killing. Cause I know a wonderful little lady who I trust and pray will be waiting for his return home.”

Corresponding during wartime also presented challenges to maintain a steady supply of stationery and rations while also monitoring your payments home. At times my grandfather had poor quality stationary or was without paper to write a letter. In a letter written on 25 Feb 1945 while fighting in Germany he suggested the following to avoid the shortage of stationary:

“Guess you either want to throw me out or jump at this new idea of mine. There is one thing certain, I can’t write on stationary unless I have stationary to write on. So I decided to start writing on the back of your letter then we will always have our letters after I get back. Sure hope you will like the idea cause by the time I hear an answer from you I’ll have written lots on your stationary-Ok?”

In a letter dated 7 June 1944 Ed provided a very detailed description of his salary and the allotments while completing his infantry training at Camp Shelby:

“Now honey in answer to a few questions that you ask me in some of your letters. One of the first things that I can think to answer is about the allotment money that goes home to mother! Now I have been a corporal for a long time my base pay is $66.00 per month. Now the army takes $22.00 out of my $66.00 leaving me $44.00 with that $22.00 they take from me they add $15.00 govt. money and mail mother a check for $37.00. When she receives the $37.00 she takes $15.00 for herself (that’s what the govt. gives her) and puts the other $22.00 in the bank in my name so now maby you can see that she doesn’t take a penny of my hard earned money.”

In a letter dated 27 Jan 1945, Ed provided a useful description of the allotments process and an interesting list of his rations while still in France:

“Gosh we have been having a heck of a time trying to learn to count all these new moneys. First the English with their pounds, shillings, and pence. Now the French with their Francs and we are expecting to have to learn the other types sometime in the future. But now don’t get me wrong about this money situation cause we don’t hardly draw any when our pay days do come. See all the boys have these allotments made out to their parents and wives, or rather have all their dough sent to their homes and then over here we stay broke all the time. But we don’t need money cause there is no place to spend it. All we need is enough to buy our weekly rations of from 5 to 7 packs of cigarettes, 4 bars of candy, 1 cake of soap and a few other articles we get once a month, such as a little stationary, ink, lighter fluid, and essential articles. We get enough of everything to make out with. The only essential we need from home is letters and a package occasionally.”

By 13 August 1945, Ed and Jean were married and he remained a Staff Sergeant. He provided Jean an update on his salary and allotment allocation:

“So when all this pay roll gets straight it will look like this—1 check to Jean F. Hill Walkertown for $50.00. 1 check to Louise M. Hill W. Cove for $37.00 and I’ll draw around $72.50 per mo.”

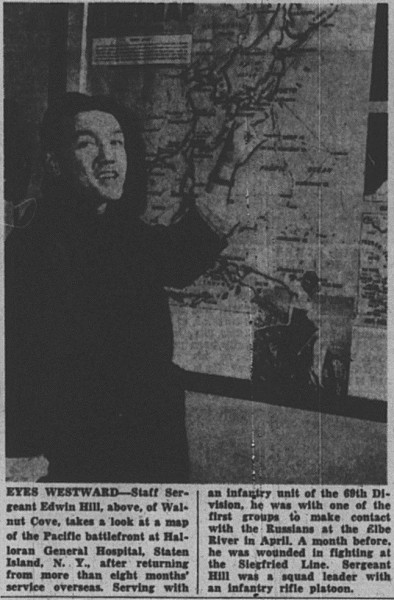

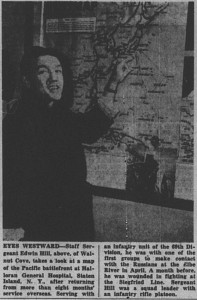

Despite the daily challenge of carrying on like a good soldier even when no mail came or he had no stationary to write, my grandfather still maintained his sense of humor and surprisingly never offered many details about his daily military situation once he entered the ETO in November 1944—honoring the US Army’s censorship restrictions. The 69th entered Le Havre France by 23 January 1945 and gradually moved through the country before a quick transit through Belgium before my grandfather entered Germany on or before 13 February 1945 for the push towards Berlin. In early March, my grandfather suffered a shrapnel wound to one of his legs in fighting “at the Siegfried line” earning him a Purple Heart that he sent home and by the end of the month he earned the rank of Staff Sergeant.

In the first few weeks of April 1945 my grandfather continued his soldier duties while also enduring an unknown illness to him until he officially went on sick call by late 17 or 18 April. His last letter from Germany was dated 16 April. His next letter was dated 3 May from a hospital in England after being flown from Germany to Paris and then onward to London. There he was officially diagnosed with hepatitis. He would spend the remainder of his time in Manchester England until mid-June when he returned to Staten Island on board the SS Santa Rosa. He spent several days at the Halloran General Hospital in New Jersey before being sent on a train to the US Army’s Battey General Hospital located in Rome Georgia. He enjoyed a lengthy furlough in July that included his marriage to Jean on 14 July 1945 followed by a brief honeymoon. He would return to Battey General Hospital where he remained until being sent to Fort Oglethorpe Georgia in early November 1945 which served as a redistribution center that processed GI’s to new assignments and to assist in discharging other servicemen. He departed Fort Oglethorpe on 13 November and arrived at Fort Bragg NC on 14 November where he was officially discharged on 17 November 1945.

From start to finish my grandfather had one primary goal to survive and return home to marry his sweetheart Jean. Like most of his generation he enlisted as a patriotic American who valued his freedom. He was selfless and motivated to be a good soldier–not obsessed about rank promotions—ready to sacrifice his life at all costs to protect the “home folks”. The below description from a November 29, 1944 letter sent to Jean from England is probably the best example where he expressed himself on this topic:

“Darling after reading those very very sweet letters I can’t help but think how fortunate we are even though we are so far apart. What makes me feel so good is just that I know that all my home folks are getting along fine and that the war is being fought over here, not over there. Yes the people of England have really had to take it on the chin where as all our families in America are free from all scare and don’t have to worry about bombs from the air or anything if that (matters?). That’s why I am willing to fight to know that it’s for a very clear cause and for you and my family I’d be glad to take what ever I have to in this war”

This April 25 and May 8 are dates we as Americans will once again be reminded of the many sacrifices the greatest generation undertook to ensure our freedom. My grandfather played a heroic role like so many in helping guarantee an American victory in WWII. Fortunately, his story had a fairytale ending and now serves as an inspiration to our family’s history and to our nation’s ongoing patriotic narrative. As a grandson who always enjoyed time with his grandfather and loved him dearly, I have been extremely blessed by undertaking this project. I am so thankful that my grandparents guarded these letters in an old suitcase!

Author’s Note: For anyone interested in researching a relative who served in the 69th Infantry Division consider visiting the website http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/ that contains excellent content to include photos, articles, and archived Fighting 69th Infantry Division Association Bulletins from 1952-2013. Each edition contains testimonials of many of the soldiers. Another useful source is Guido Rossi’s StoryMap titled “A World War II Infantry Recruit’s Journey through Camp Shelby” link: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=10919ce3b4724cb68b9ec1c1312dd57c